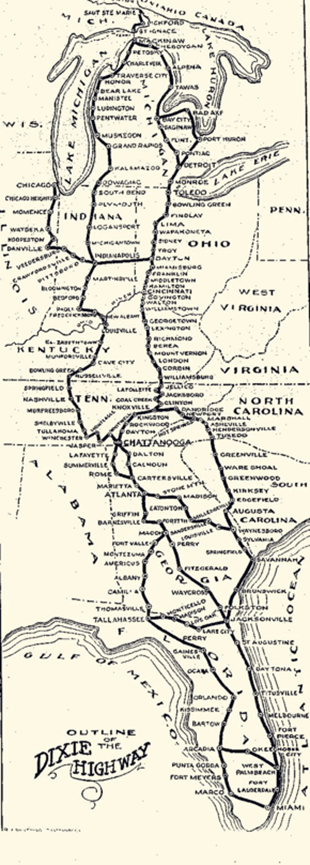

The Dixie Highway (DH) was initially conceived of in 1914 to promote the use of the auto-mobile for long distance travel from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to Miami, Florida. In 1915, when the plan was first announced by automobile pioneers and other promoters of the Progressive Era Good Roads Movement, groups committed to the improvement of the nation’s roadways, the citizens of the east and specifically South Carolina were imprisoned by impassable networks of rutted trails, most beginning as Native American paths. The southern states, still extensively rural agricultural estates of varying sizes, were mostly bound to cotton and tobacco for trade sources, and these farm to market routes were tied to the weather. Usually the roads into the farming communities radiated from the train sta-tions in order to reach the closest spot to sell crops, and farmers were often hindered from getting their harvest to market on mudways. So, being certain that these Good Roads would bring commerce and provide consistently usable roads, a period of excitement followed as towns and cities and even historic sites vied for the corridor to pass their way.

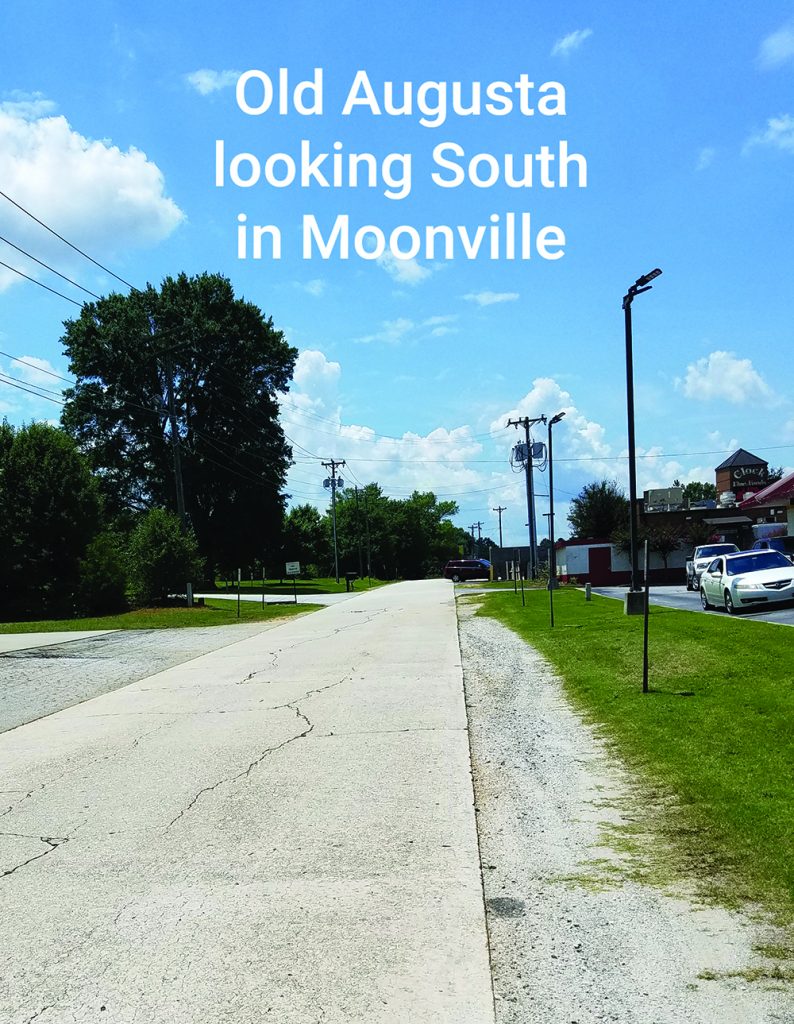

Greenvillans had moved earlier to improve the Buncombe Road to the mountains thus being ready when the Dixie Highway was proposed. To this end also, South Carolina allied with North Carolina to lobby for the modern motorway to cross the mountains onto the Bun-combe Turnpike and the Buncombe/Augusta Road both of which had already been major trade paths, post roads, and excursion routes for over a hundred years. By 1920 the route was endorsed by the Dixie Highway Association based in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Desig-nated the Eastern (sometimes Carolina) Division, the highway entered South Carolina just below Tuxedo, North Carolina, following the old traders path to Merritsville, Greenville, Moonville, Ware Place, and Princeton in Greenville County. Through Laurens County, it passed into the new mill town of Ware Shoals, then along to the train built towns of Hodges and Greenwood, next into Edgefield County through that historic town and on into Aiken County, finally to the old site of Hamburg surrounded by North Augusta before crossing into Augusta, Georgia. This modern concrete road was not concerned with the weather. Passing along it to the cotton mills and train stations became easy since the use of trucks in-stead of wagons had quickly become available to farmers and industry.

During the years from 1915 to 1925, the modern south was forged. Prior to World War I, the proposal for the Dixie Highway was basically concerned with providing vehicles with good road access to travel from north to south and back again, to sell cars and trucks, to provide good farm to market thoroughfares, and to promote general commerce. But as the war became a major concern, moving soldiers and the machinery of war became another Dixie Highway promotion. Many military bases were scattered across the south, therefore speed of movement toward shipping lanes became a point of alarm with the state of the oft muddy roads. Military preparedness was a dilemma that supported the Good Roads Movement, and therefore, the key roadway of that crusade. Federal interest in DH grew throughout the wartime. Advantage was to the southern course, since the southern roads were the most impassable, since the south had no gas taxes to support their roads, and since southern males were forced to give a certain amount of their year repairing roadways or sending someone in their stead. These southern roads were later maintained by convicts in chain gangs which became an active manner of suppression of the African American popu-lation as well as a way to fulfill local commitments to road work at a minimal cost. Initially, chain gangs were hired out in groups or leased to private individuals for a fee. Later this became unmanageable as more and more requests came in and fees ran up and not enough convicts were available. So, the road crews became part of the prison system continuing the excesses and abuses of unsupervised leases which continued into the mid-1900s.

The end of the designation Dixie Highway came in 1926 when the federal government es-tablished the early interstate United States Highway system. US Highway 25 took over South Carolina’s section of the DH, and the red and white DH signs up and down the mo-torways disappeared, leaving most that travel the old road ignorant of its history, and I am one.

I have lived near this historic road, as have my ancestors since about 1825, and no one ever spoke of the Dixie Highway or its construction. But neither did they talk about the paving of the road in front of my house. I have pictures of my Grandmother standing in the dirt where blacktop is now. There is no concrete under this macadam though, I can guarantee, which is not the case under the DH in many parts of the county. Asphalt over concrete is easy to identify. Over time the tar and gravel will give way to the harder surface of the con-crete below it, and those spacing cracks show allowing weeds to immerge in the lines. Often you can even see that the road was widened as the vegetation lines the edges of the concrete short of the sides of the macadam. On stretches of the paved over concrete where the way is still traveled, weeds aren’t growing but the gaps are visible and usually felt. You know, the old concrete roads could just drive you crazy with the continuous bump,

bump, bump…♦