If you drive past Fountain Inn resident Pam Lewis’ home, you might see a flag flying that is unfamiliar to you. It’s black and white and rather solemn-looking. The flag contains the acronyms POW and MIA standing for prisoner of war and missing in action. “You are not forgotten,” it also reads. Indeed Frankie Johnson, Lewis’ brother, is not forgotten, though he has been missing for the last 47 years.

Editors Note: On this Memorial Day, I thought it was appropriate to recognize the ultimate sacrifice made by Sgt. Frankie B. Johnson Junior. This tribute was published in June 2015. The article was eloquently written by former Sentinel writer Kenny Maple.

Sgt. Frankie Burnett Johnson, Jr. was a soldier with the United States Army. He was drafted and sent to war in South Vietnam. He wasn’t overjoyed about going; most people weren’t, but he was proud to serve his country. Johnson was like many soldiers- young, full of life, enjoyed receiving mail, especially his sister’s cookies. He enjoyed playing the guitar and chasing girls.

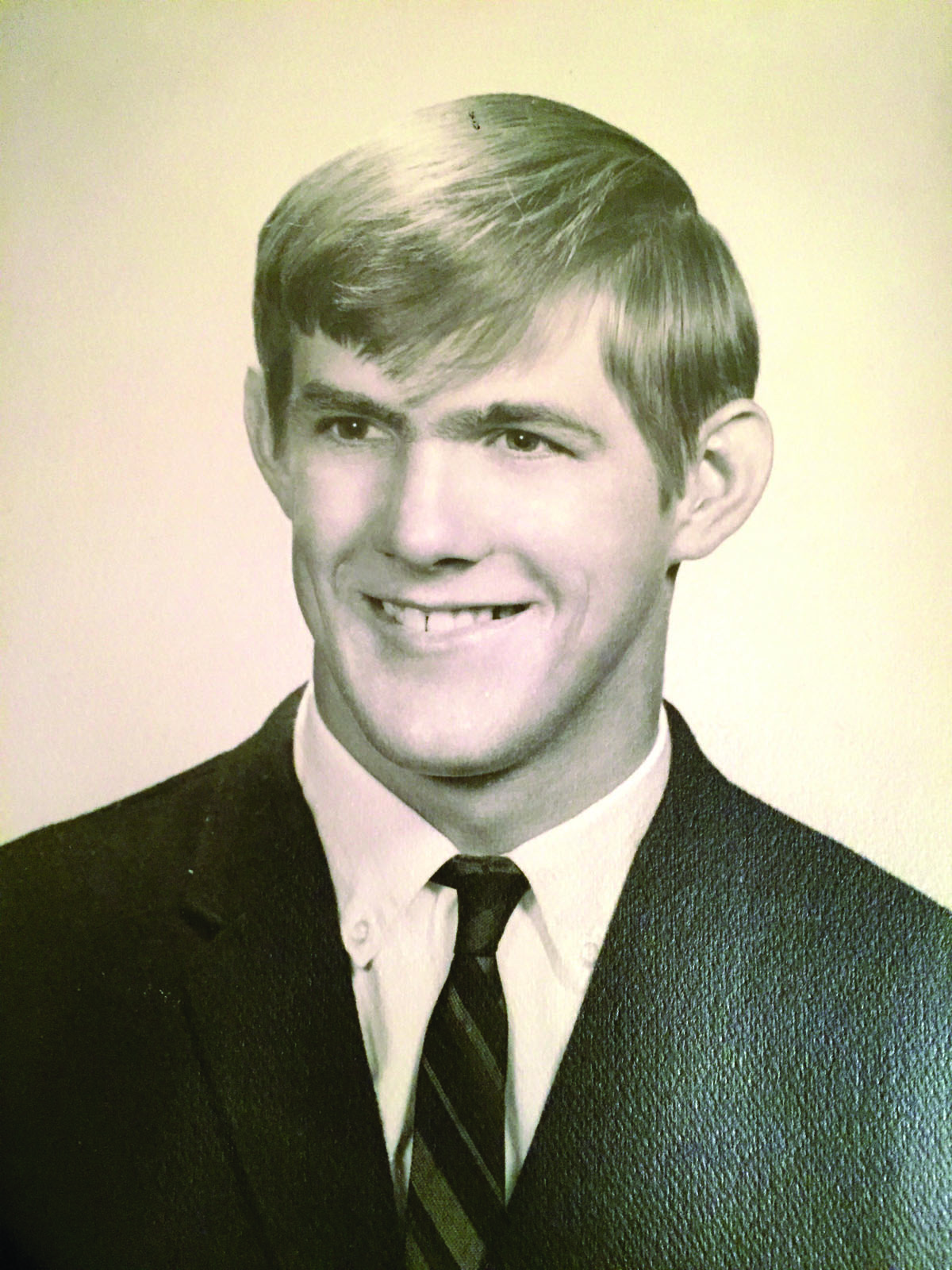

High School yearbook portrait

“He was just typical 19-year-old boy,” Lewis said, gazing at old photographs of her brother. “He was a happy person. He loved country music and loved to work on old cars and drive a tractor.”

Indeed within photographs Johnson does appear to be a happy young man. You would be hard-pressed to find a picture where he is not smiling. His smile causes a smile to splash across his sister’s face.

“We mothered him to death,” she said, “and he tormented us when he got to be a teenager and had three teenage sisters,” she said, laughing as she mentioned Johnson’s propensity for playing pranks and attempting to embarrass his sisters in front of their suitors.

“You wonder what he would have been like,” she pondered aloud, “if Frankie were alive and would have gotten married and had children and grandchildren.”

Her voice tails off. Thinking about the “what might have been” is either too painful or too open-ended. Either way, it’s clear she misses her brother, as does the entire family. Their parents, Frank and Bonnie Johnson, have been gone for quite some time, but Lewis said their faith kept them strong as they dealt with the news or lack thereof concerning their son. They held out hope concerning their loved one. “We’ll know something soon,” she said they kept being told.

The family took it hard, Lewis especially. She remembers when she received the call from her mother about Johnson’s helicopter being shot down. He was only four to six months from coming home. That was April 21, 1968.

“I hit the couch and didn’t get off of it for about three weeks,” she said, voice quivering. “I just didn’t function well because Frankie and I were real close. We all were real tight.”

Few details emerged over the following days and weeks. Johnson had been the crew chief of a helicopter headed to a combat support mission over a southern province in Vietnam. On board with him was his best friend, Larry Jamerson, from Rosman, North Carolina. Pilot Robert C. Link, Capt. Floyd W. Olsen and technicians Lyle E. MacKedanz and James E. Creamer also joined him. While in route, inclement weather and a tactical situation caused the mission to be aborted. Olsen reported this from the helicopter, but the crew never returned to base. Communication with the aircraft was attempted but unsuccessful. It is believed that the helicopter was shot down. On May 27 of that year, a ground team found the main rotor blades about 200 meters west of the tail boom, but they could not locate the main cabin before coming under enemy fire and being forced to depart the area. All crewmembers were unaccounted for; located Army dog tags were their only evidence. The tags were Johnson’s. They were found in a non-US truck.

At the time, Johnson was just 20 years old. Lewis still has received no explanation as to why Johnson’s dog tags were found in the truck. “We’ve never gotten an answer,” she said, mentioning, too, that she doesn’t know of the whereabouts of the tags now. They were never given to her.

What she does have from her brother is his khakis from the war. She also treasures her photo albums, which take up the majority of a bookshelf. This is how she remembers her brother. Occasionally she receives letters from Army informing her of meetings for those POW/MIA families. Sometimes she goes, if the meetings are nearby. What she really appreciates is the support of friends and complete strangers who have heard about her brother or who support those soldiers who never returned home. Bracelets have been made up over the years bearing the name of Frankie Johnson or other POW/ MIA soldiers. Within a stack of papers printed from a website called “The Virtual Wall,” Lewis has several kind comments from people who lend their prayers and support. Wrote one anonymous individual in 2002: “This is a thank you to Frankie and all the men and women who served in our Armed Forces. I have been wearing Frankie’s bracelet since I was 19 years old. I am now 35. I hope one day closure can come to all of us who still hope and pray for Frankie and all the MIA’s (sp). You are not forgotten, Frankie, and never will be. God bless the Johnson family, and God Bless America.”

Though Johnson’s helicopter went down in 1968, his memorial wasn’t until 1978. Visitors to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial will find his name there. He also has a military stone in his memory within the Beulah Baptist Church Cemetery in Fountain Inn.

“My big thing has always been after you get past the fact that you know he’s not coming home, which eventually you do get past it and you know it in your heart and you accept it, but you don’t ever get used to the idea,” Lewis said tearfully. “And now it’s been 47 years since he’s been gone.”

Though plenty of individuals know Lewis’ story of her lost brother from reports released online or from visits to the memorials, those don’t tell the full story. Reports don’t tell of his fondness of country music or playing his six-string. Reports don’t tell of how he enjoyed tinkering with old cars, like he used to do at the old Datsun auto shop. More importantly, reports don’t tell of this smiling young man’s love for his family and their love for him. They all miss him.

In addition to Lewis, Johnson is survived by her brother J. Eric Johnson and sister Dale Abercrombie. They still live in Fountain Inn. Other siblings, Rusty Johnson and Judy Mahaffey, have since passed.

The family would like to thank everybody who wore his bracelet and have not forgotten him.